The Meiji Revival

Tachibana Yasukuni and the Botanical Soul of Japan

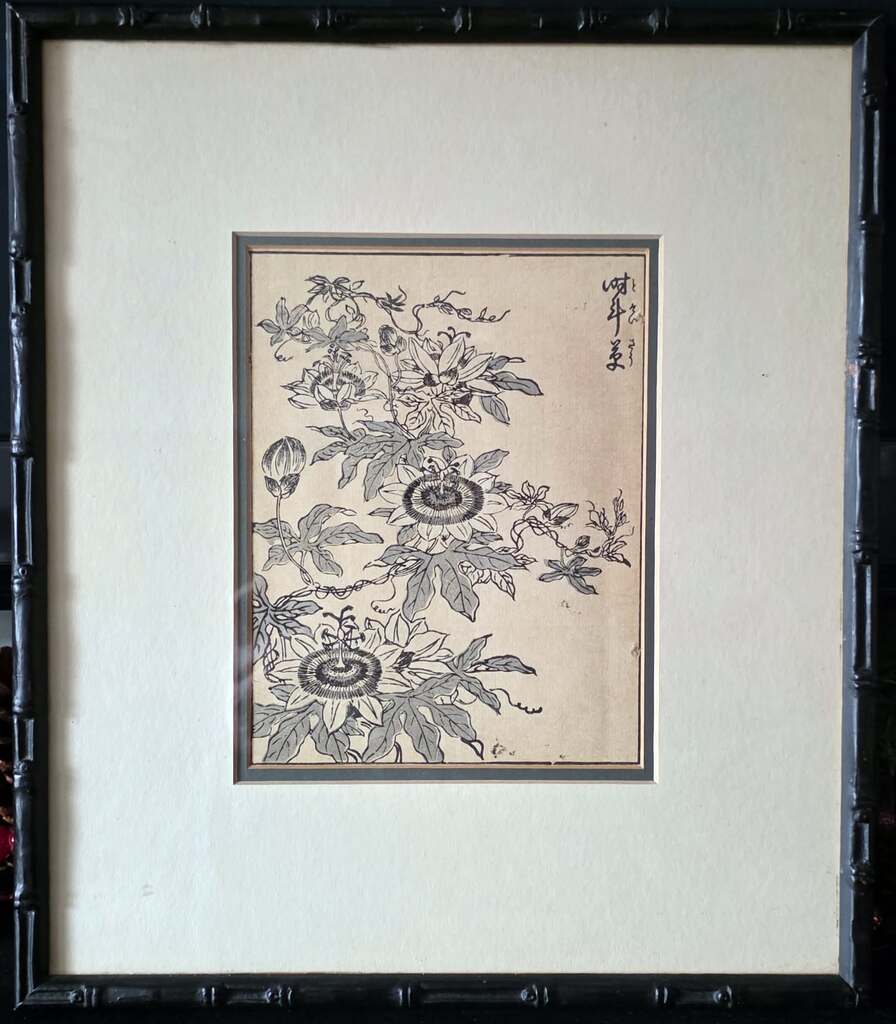

In the late 19th century, Japan stood at a crossroads. As steamships replaced sails, the nation paused to preserve its artistic heritage, resulting in exquisite reprints, like this beautiful pair of Yasukuni’s from 1890. This era, explored deeply in our previous study, Beyond the Floating World, saw the technical brilliance of urban Ukiyo-e turn its gaze toward the tranquil poetry of the mountain field.

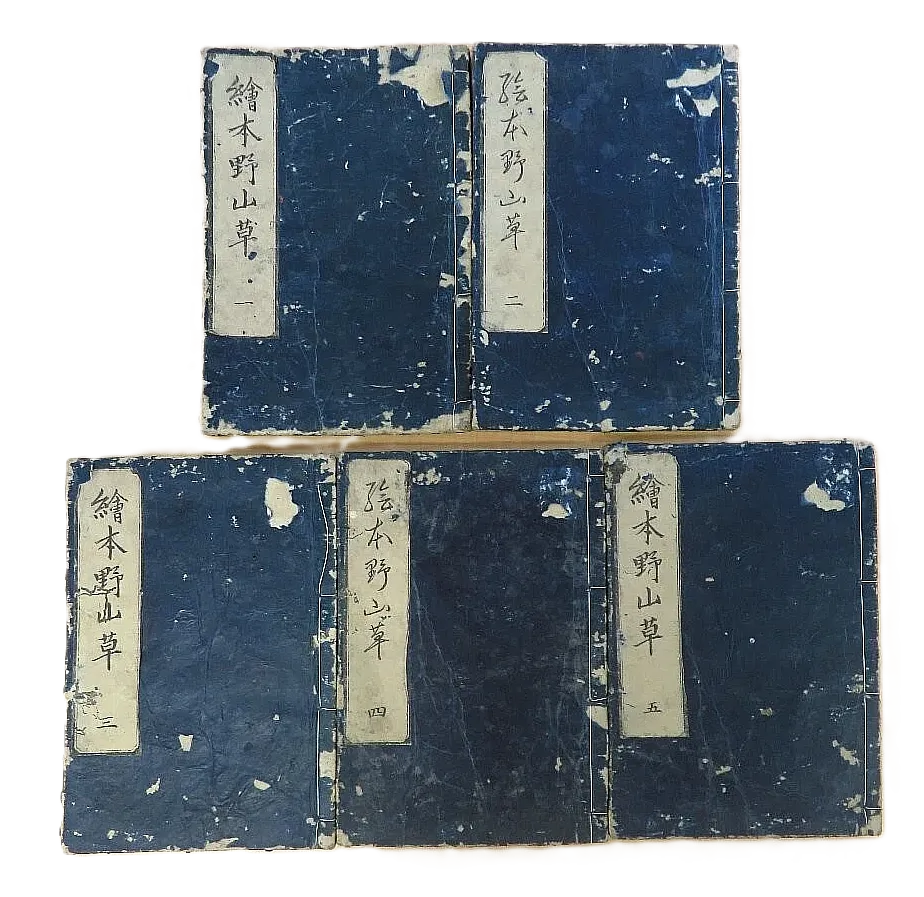

The Artifact Profile

| Category: | Woodblock Print |

| Artist: | Tachibana Yasukuni (Hōkyō rank, 1715–1792) |

| Era: | Meiji Period (Original 1755 designs; this edition c. 1890) |

| Series: | Ehon Noyama Gusa (Plants of the Fields & Mountains) |

| Media: | Hand-carved woodblock (Mokuhanga) on washi paper |

| Style: | Kacho-ga (Traditional Bird-and-Flower Painting) |

The Stories in the Ink: Expanded Narratives

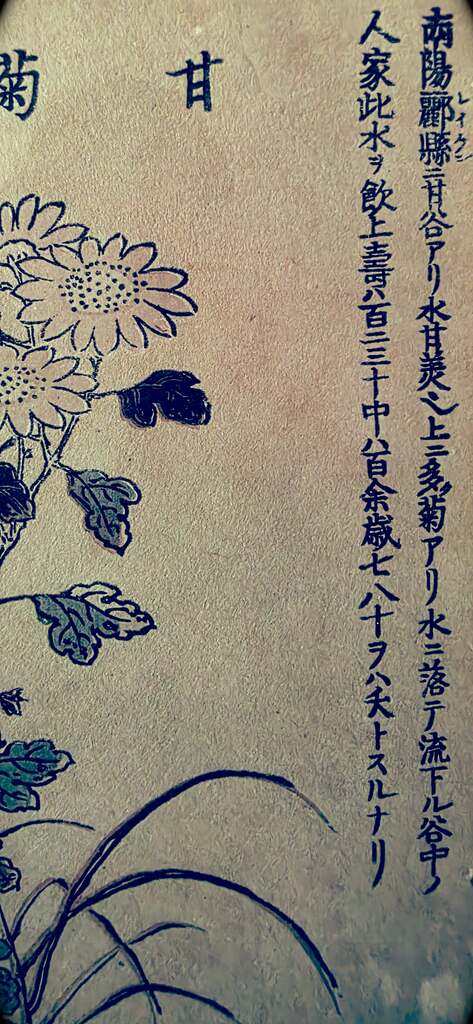

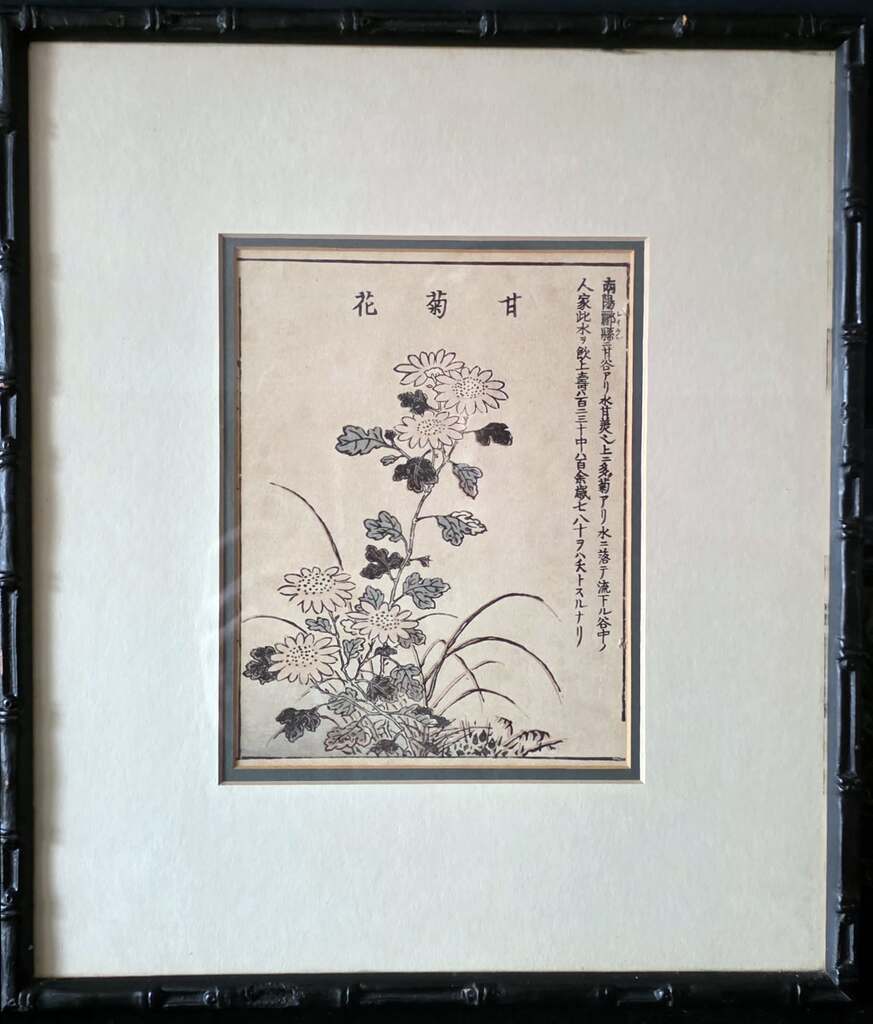

1. The Secret of Nanyang (The Sweet Chrysanthemum)

The vertical text on the Sweet Chrysanthemum print (Kankiku) is more than a label; it is a fragment of ancient prose. It references the Sweet Water Valley of Nanyang County, a place of Taoist myth where the mountain streams were choked with wild chrysanthemum petals.

According to the legend, the petals infused the water with a life-extending “dew.” Residents who drank from the stream reportedly lived to 140 years of age. By the Meiji era, this story had shifted from pure myth to a symbol of Japan’s own national “rejuvenation.”

For the 19th-century collector, this print wasn’t just botanical art; it was a visual talisman for longevity and a celebration of the Emperor’s crest—the 16-petaled Kiku—blooming with renewed vigor in a modern age.

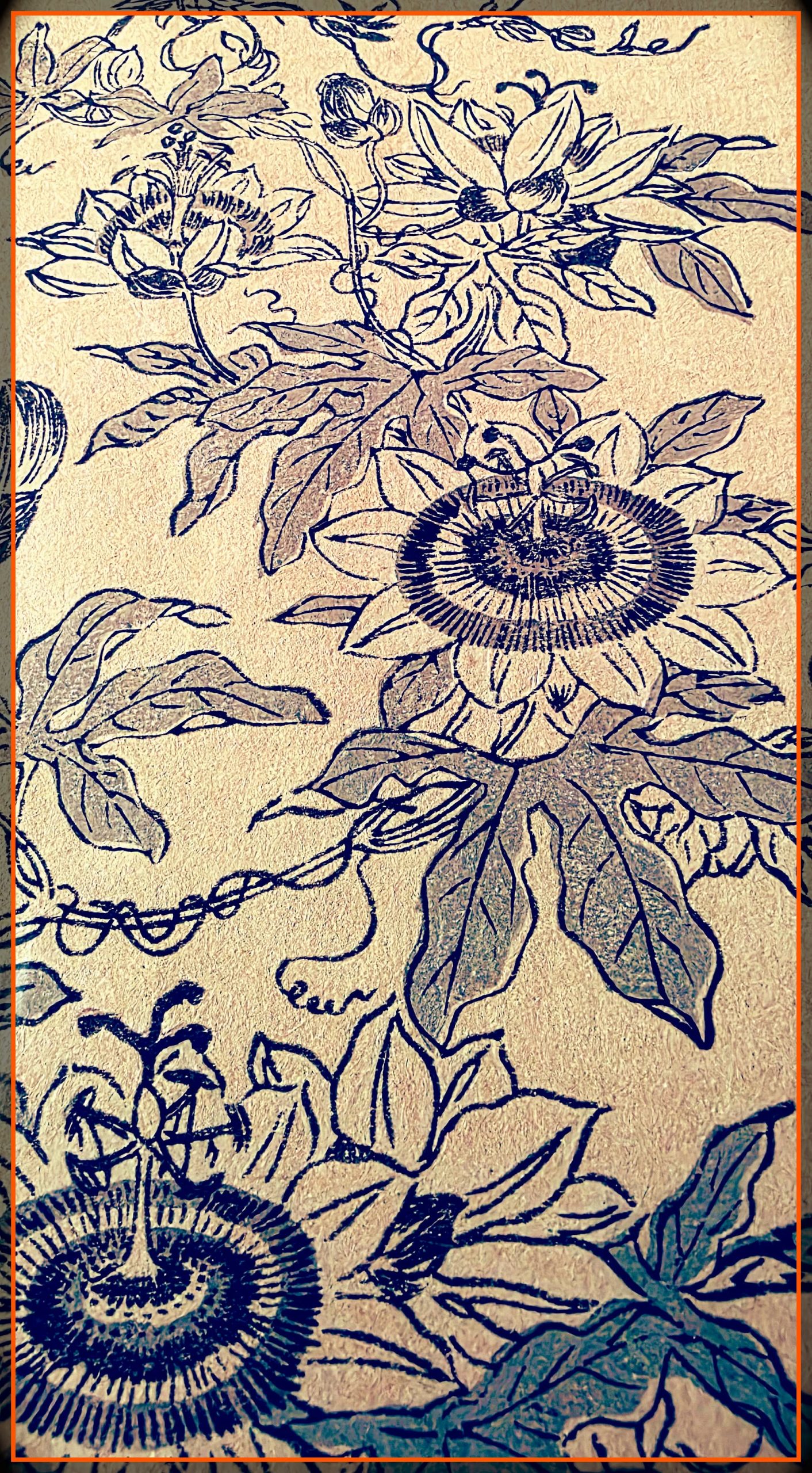

2. The Clock of the Cross (The Passion Flower)

The Passion Flower (Tokeiso) tells a story of global collision and linguistic adaptation. When Western missionaries first brought the flower to Asian shores, they utilized it as a pedagogical tool, seeing the “Passion of Christ” in its anatomy (the three styles as nails, the corona as the crown of thorns).

However, the Japanese eye, as captured by Yasukuni, saw something far more industrial: Mechanical Time.

During the Meiji period, Japan was rapidly adopting Western timekeeping standards. The flower’s perfectly radial symmetry reminded observers of the newly imported pocket watches and clock towers appearing in Tokyo. By naming it the “Clock Plant,” the Japanese effectively “domesticated” a foreign religious symbol, turning it into a metaphor for the precise, rhythmic nature of the modern world.

3. The Hōkyō’s Vision: Elevating the “Common” Weed

The series title, Ehon Noyama Gusa, reveals the radical intent of the artist. Before Yasukuni, high-ranking Kano School painters—who held the elite Hōkyō (“Bridge of the Law”) rank—primarily focused on grand, mythical subjects: dragons, phoenixes, and Chinese sages.

Yasukuni’s series (shown above) was a “democratization” of beauty. He took the prestigious techniques of the Shogun’s court and applied them to the “Plants of the Fields and Mountains.” He argued that the divine was not found only in myths, but in the structural integrity of a mountain vine. This philosophy is the true link to the “Floating World”—the realization that the most fleeting, humble wildflowers are the most worthy of our artistic devotion.

The Collector’s View

The physical nature of these prints confirms their c. 1890 provenance.

- Archival Evidence: As seen in the provided photo data, the original gallery label on the reverse identifies these as “Hand-printed in Japan,” a mark of the high-quality Meiji export market.

- The Framing Aesthetic: The black lacquered faux-bamboo frames are quintessential “Japonisme.” This style became a sensation in European design circles, specifically to house woodblock prints. The frames were meant to echo the organic geometry of the plants themselves.

- The Woodblock “Bite”: Upon close inspection, the ink has a slight “embossed” quality. In Mokuhanga, the carver removes the negative space, leaving the design in relief. The paper is then pressed onto the block by hand using a baren (a circular pad), which pushes the ink deep into the mulberry fibers, creating a soft, painterly texture that digital reproduction cannot achieve.

Design Summary

These prints are a masterclass in purposeful minimalism. For a modern space, they offer a narrative of longevity and time, wrapped in a 130-year-old patina that modern digital prints simply cannot mimic. They remain a vital link to a time when Japan was teaching the rest of the world how to truly “see” nature.